Christians more interested than Jews over where Mount Sinai actually was

Saint Catherine’s Monastery with Willow Peak, traditionally considered Mount Horeb, or Mount Sinai, in the background. Credit: Joonas Plaan/Wikipedia.

by Sarah Ogince

(JNS) — When the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization designated the “Saint Catherine Area” as a World Heritage Site in 2002, UNESCO noted that the Greek Orthodox monastery “stands at the foot of Mount Horeb where, the Old Testament records, Moses received the Tablets of the Law.”

“The mountain is known and revered by Muslims as Jebel Musa. The entire area is sacred to three world religions: Christianity, Islam and Judaism,” the U.N. agency adds. “The monastery, founded in the sixth century, is the oldest Christian monastery still in use for its initial function.”

But it’s not at all clear that the tiny fortress in the desert, which is dedicated to the martyred Christian saint Catherine of Alexandria, and which has drawn pilgrims and scholars to Egypt for centuries, is actually sacred to Judaism, as the U.N. agency suggests.

Ahead of the two-day holiday of Shavuot (it begins this year after sundown on June 11 and continues until nightfall on June 13), which marks the receiving of the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, experts told JNS that many Jews believe that the site of the revelation at Sinai, which is also where Moses encountered the miraculous burning bush, is unknown today by divine design.

Biblical accuracy

Mount Sinai has long been an object of veneration, curiosity and speculation for Christians, according to Mark Janzen, associate professor of archeology and ancient history at Lipscomb University, a private Christian school in Nashville, Tenn.

“For many Protestants, Sinai is connected with the doctrines of Inspiration and Inerrancy, the idea that the Bible is accurate in all of its truth claims,” he told JNS. “We’re invested in it.”

Claims that Jebel Musa (Arabic for “Mountain of Moses”) is the biblical Mount Sinai are recorded as early as the fourth century, records Joseph Hobbs, professor emeritus of geography at the University of Missouri-Columbia, in the 1995 book Mount Sinai.

Modern archeologists, who have sought to trace the path upon which the Israelites walked after the Exodus from Egypt, have largely supported the claim, according to Janzen.

“There has been a lot of research on the length of a day’s journey,” he said. “Southern Sinai seems to be about the correct distance if we take seriously the itinerary in the scripture.”

There are also water sources near the mountain; Jewish scripture describes a stream flowing down it, noted Janzen. (According to Exodus 32:20, Moses reduced the Golden Calf at the foot of the mountain to dust, cast it “upon the water” and made the Israelites drink it.)

Several peaks in the area fit the biblical criteria for Mount Sinai, but Jebel Musa remains “the consensus among most Christians,” according to Janzen.

In fact, tens of other alpine candidates have been proposed as the holy mountain, including some peaks in Saudi Arabia, but scholars have noted the large open spaces at the foot of Jebel Musa that could have accommodated 600,000 Israelites, or even perhaps millions, to congregate there.

Those who believe Jebel Musa to be the biblical Mount Sinai also cite a large and ancient raspberry-like bramble in the courtyard of the monastery at the foot of Jebel Musa. Hobbs identifies the bush as rubus sanctus, and it is believed to be the burning bush from which God spoke to Moses, charging him to confront Pharaoh and then lead the Israelites out of Egypt.

Vast sacred art collection

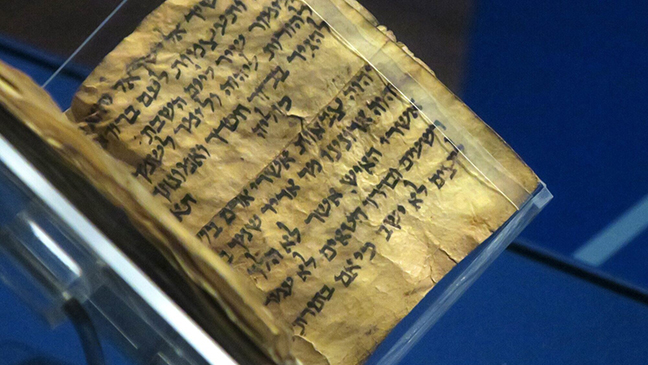

The monastery at the foot of the mountain houses a large collection of religious art and manuscripts, many of which have traveled for exhibitions at major museums in the United States and overseas. Sacred objects that were formerly in the monastery’s collection have also found their way into museum collections.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt, which many Christians believe is at the site of Mount Sinai. Pictured is what many believe was the burning bush from the Bible. Credit: Dale Gillard/Wikipedia.

The themes of the burning bush and Moses receiving the Ten Commandments feature prominently in the monastery’s collection, according to Alice Sullivan, assistant professor of art history and architecture at Tufts University in Medford, Mass.

“The monastery remains a powerful site of Christian values and beliefs that celebrates the figure of Moses and his encounters with the divine,” she told JNS. “It also mediates between events in the Old Testament and the New.” (Many scholars refer to Jewish scripture as the “Old Testament,” although many Jews eschew that term.)

Sullivan is co-director of the Sinai Digital Archive, which makes the monastery’s collection available online. “This website brings together for the first time the photographic archives from the Michigan-Princeton-Alexandria Expeditions to Sinai in 1956, 1958, 1960, 1963 and 1965, now held in the Visual Resources Collections at Princeton University and the University of Michigan,” per the site.

Combining depictions of Moses and the monastery’s patron saint, who many Christians believe to have been transported miraculously to Mount Sinai after her martyrdom, asserts continuity between Christianity and Judaism, according to scholars.

“Christians have historically taken a strong interest in apologetics and in defending the faith,” Janzen said.

Intentional ambiguity

Jews think of the site beneath and surrounding the monastery—and of the Mount Sinai of the Torah that is at the center of Shavuot—in a rather different way.

For most of Jewish history, Jews have shown little interest in returning to the scene of the Revelation in Exodus—a mountain the Talmud and Midrash describe as lowly and overshadowed by more arrogant peaks. A popular Jewish children’s song tells of mountains competing for the honor of hosting the Torah. The humblest underdog turned out to be the Little Mountain That Could.

The Talmud records in Bava Batra (74a), in one of the fantastical stories of the travels of Rabbah bar bar Chanah that are typically viewed allegorically, Rabbah accepted an Arab guide’s offer to take him to Mount Sinai. “I went and saw that it was full of scorpions as tall as donkeys,” the passage records, in Aramaic.

Most rabbinic authorities have declared the precise location of the mountain lost, according to Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz, the senior religious leader of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun, a more than 150-year-old Modern Orthodox synagogue on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

“Mount Sinai loses its meaning after the revelation,” Steinmetz told JNS. “There’s no religious value attached to it. It’s fascinating.”

Judaism doesn’t prohibit returning to Mount Sinai, and rabbis have occasionally joined the ranks of the mountain hunters, but there is reason to believe that God would rather they didn’t search for it, according to Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky, of Ansche Chesed, a “egalitarian, Conservative synagogue” on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

The last intrepid biblical visitor to the mountain was the prophet Elijah, who did not get a warm reception from God when he did so in the book of Kings, according to Kalmanofsky.

“The revelation he gets there is ‘a still small voice,’ not exactly a communal experience,” Kalmanofsky said.

Judaism has a strong tradition of pilgrimage and communal gathering at sacred places, such as the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, he added. But Mount Sinai’s location in the untracked wilderness represents “the other side of the coin,” a more individualistic approach to spirituality, he said.

Medieval commentaries noted that the Torah was given in the wilderness so that it would be accessible to all, and Steinmetz notes that even more ambiguity surrounds the biblical event.

Although rabbinic sources connect the revelation at Sinai to the sixth of the month of Sivan, the date of the Shavuot holiday, the Torah doesn’t specify the date when the Torah was given, according to Steinmetz. “It has a certain metaphysical aspect to it,” he said. “You get the sense that Torah is supposed to be something that is above time and above place.”